I’m a simple girl, and when life allows it, I become a creature of habit; I wake up the same way every day: my phone rings, I snooze it five times, panic, start the coffee, and open my three email accounts to get my blood pressure going. Then I delay work for a bit, play music, and sip coffee until the anxiety builds up enough to make me productive.

The early Zagreb-Vienna-Pristina flights disrupted the routine, but I still woke up early enough to have my much-needed morning coffee and a cigarette. On my way to Kosovo, I couldn't help but wonder how horribly dangerous the perceptions are. When I told people where I was going to, the first reaction was usually a mix of confusion and concern. Why? followed closely by Is it safe? and then the classic What is there even to do? Turns out, a lot. So, while my mom worried about my safety, I worried about whether I could still smoke inside. No need for either concern.

We landed at Pristina airport with a welcome sign that wasn’t quite sure what language to greet us in. We weren’t sure either. Then, arriving in Prizren, I realized I had unknowingly arrived in a paradise for anyone interested in language politics. I was also overwhelmed by the visual chaos – something between nostalgia, a (re)construction site, and an aesthetic eclectic maximalism. The don’t judge a book by its cover in the Balkans translates to don’t judge a house by its façade.

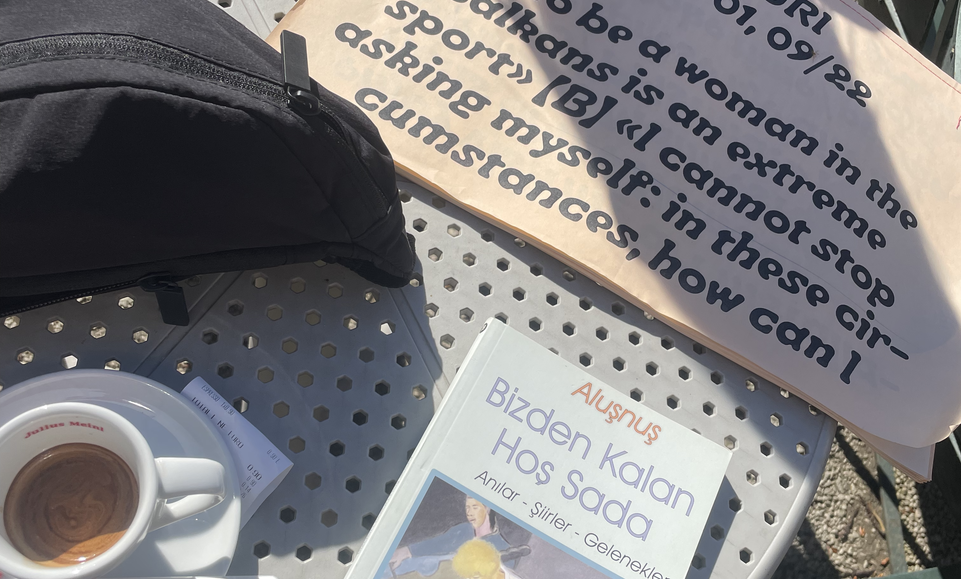

Someone told me, Prizren is a city of cafés and open spaces—things happen here. And I saw it. By now, we have found our go-to places in the city, and our conversations over coffee turned into work, because thinking about cultural spaces happens best in spaces that aren’t meant (or perceived) to be cultural. They sometimes emerge in places where they’re least expected – or, more precisely, in places some might dismiss as such.

I must say I’ve always hated working from home, and found the libraries too sterile and quiet for my liking. For me, a bar works better as an open office. Preferably dark, smoky, with bad coffee, and a plastic spoon to chew on. For some, it’s proof that people are just wasting time instead of being "productive." But for others, it’s the only real infrastructure for gathering, working, discussing, and resisting. What’s a café if not a space of strategy?

Café, bar, kafić, kavana – not going into the differences here, call it as you like – is not only a leisure time space, it is a space where you gather to discuss ideas, make plans, write exhibition proposals, and take online meetings. Maybe you stumble into an artist or a philosopher, get existential over a cup of rakija. It’s also a way of reclaiming time, of resisting the logic of productivity that demands constant busyness. And then there is a whole historical framework of cafes as meeting points of artists, revolutionaries, intellectuals. What if this, too, is a form of cultural work, just one that doesn’t immediately translate into reports and funding applications?

What is a cultural institution anyway? Must we define culture before defining its space? Inhabiting a cultural space, occupying it, creating it – what’s the difference? Bourdieu would say that habitus shapes our perception, our sense of belonging. When the idea of what culture is mirrors nation-states, and globalization erases fixed definitions, what happens to cultural spaces?

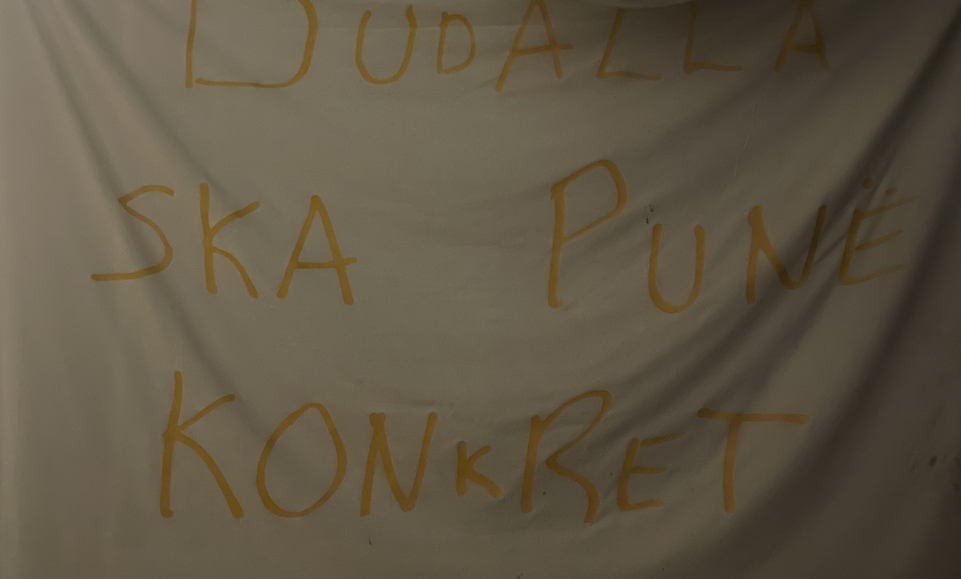

Lumbardhi’s café, where we gather to work and watch movies, for example, seems like an institution within an institution, an intersection of informal gathering and structured programming. A reminder that cultural spaces exist in tension, between precarity and permanence, between the need for sustainability and the impossibility of stability. The Lumbardhi Cinema, once threatened with closure, now stands as a testament to what happens when people refuse to let go, although still in an unenviable situation with the upcoming renovation.

So, in a world where cultural spaces are always at risk of being swallowed by gentrification or political turmoil, I have to ask: What makes a place truly cultural? Is it the history, the people, or simply the stories we choose to tell in it?

Then there’s the question of who gets to move through these spaces freely. It’s easy to romanticize cultural spaces when you don’t have to fight for them. This made me think: what does it mean to engage with a space that others struggle to claim as their own? It’s about how culture survives in places where permanence is never guaranteed.

And I admit, I found myself slipping into the role of the privileged foreigner, strolling through Prizren with a certain naïve charm – thinking, maybe even saying to myself, “Oh, I could totally stay here a bit longer.” But even the thought of offering someone advice on how to rethink their own cultural space would feel like a small act of violence. To suggest that someone should change their relationship to their own surroundings, to question the space they’ve inhabited all their lives, feels a little too presumptuous. I’m not interested in that kind of espresso diplomacy. Especially knowing I can leave whenever I want, with my privileged EU passport to carry me back home.

I am here as a guest, with the freedom to move in and out, to romanticize the slowness, the aesthetics, the linguistic diversity – while for many people here, the same borders I crossed to get here dictate where they can and cannot exist.

Anyway, there’s nothing simple about culture and cultural spaces. Not here, not anywhere.

On the other side, now it has been two weeks, and I probably literally had more coffee than water, which called my insomnia back into her life, and just like that, Prizren became a city to be awake at. Maybe in the next weeks I'll have more answers than questions.

What I was trying to say is Prizren isn’t a postcard, it's a conversation.